‘It has all paid off’

Wilfred and Rosemarie Willier reflect on a lifetime of faith together

Wilfred and Rosemarie Willier are a testament to the endurance of both faith and love.

They share similarly unique backgrounds, as former students of the Indian Residential Schools system and as passionate devotees of their Catholic faith. They’ve lived a long and fulfilling life together, having raised a family and championed many causes and programs for their community.

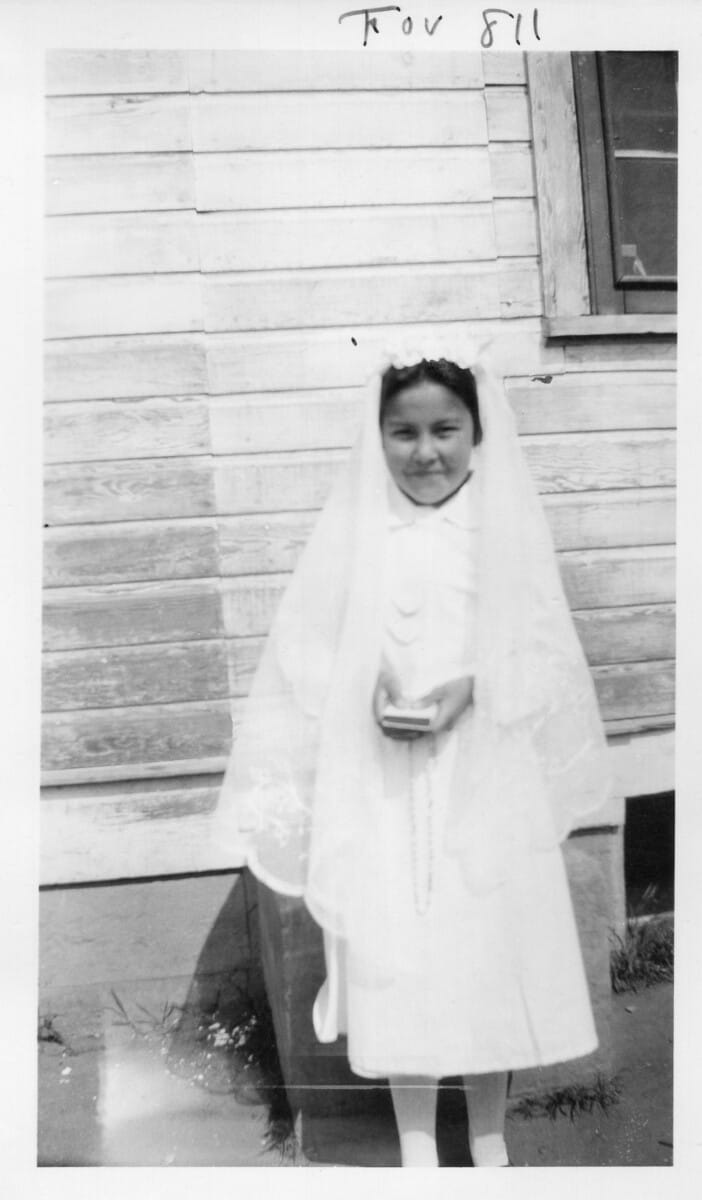

Raised on opposing ends of the Peace Country – Rosemarie in the northwest regions of Fort Vermillion and Hay Lakes, and Wilfred in the northeastern mission of Joussard – it was only by a providential coincidence that the couple ever met.

Fittingly, they first came into contact with one another while attending Mass away from home – at Our Lady of Fatima Church in Sucker Creek on Easter Sunday, 1954. At that time, Wilfred was working full-time with the Northern Alberta Railroad (which was later bought by CN Rail). Away from home and on the job, Sucker Creek was the nearest community for him to attend Easter Mass that day. Rosemarie at that time was on a break from school in Grande Prairie, and decided to spend her time off with a classmate from the Sucker Creek reserve.

In those days there was a priest from the mission in Joussard who would come to Sucker Creek to celebrate Mass every 2nd and 4th Sunday, and of course at special times of year like Easter and Christmas.

That Mass was where Wilfred and Rosemarie first met. But it was only when they ran into each other a second time that Wilfred asked her out for a date. Rosemarie admits that before she was ready to say yes, she approached a Sister of Providence who they both knew, and asked the sister if Wilfred was a decent man and a good Catholic. The sister assured her he was, and the date went ahead.

Rosemarie returned to Grande Prairie to continue her schooling and they began writing letters to each other. Wilfred eventually visited Grande Prairie for a second date – a drive to Lake Saskatoon – and this time a Sister of Providence joined them for the excursion. As they reflect on it now, Rosemarie notes this date may have impressed the sister more than anyone else. Before his trip, Wilfred’s niece had left a collection of her earrings in his car. The nun had mistaken them for a collection of medals, and, thinking he must have been a grand champion of sorts, boasted of them to Rosemarie.

This open companionship with the Sisters of Providence reflected the mutual affinity and affection Wilfred and Rosemarie had for the Catholic nuns who taught them. They had both spent much of their youth in the Indian Residential School system, where they were taught by Sisters of Providence.

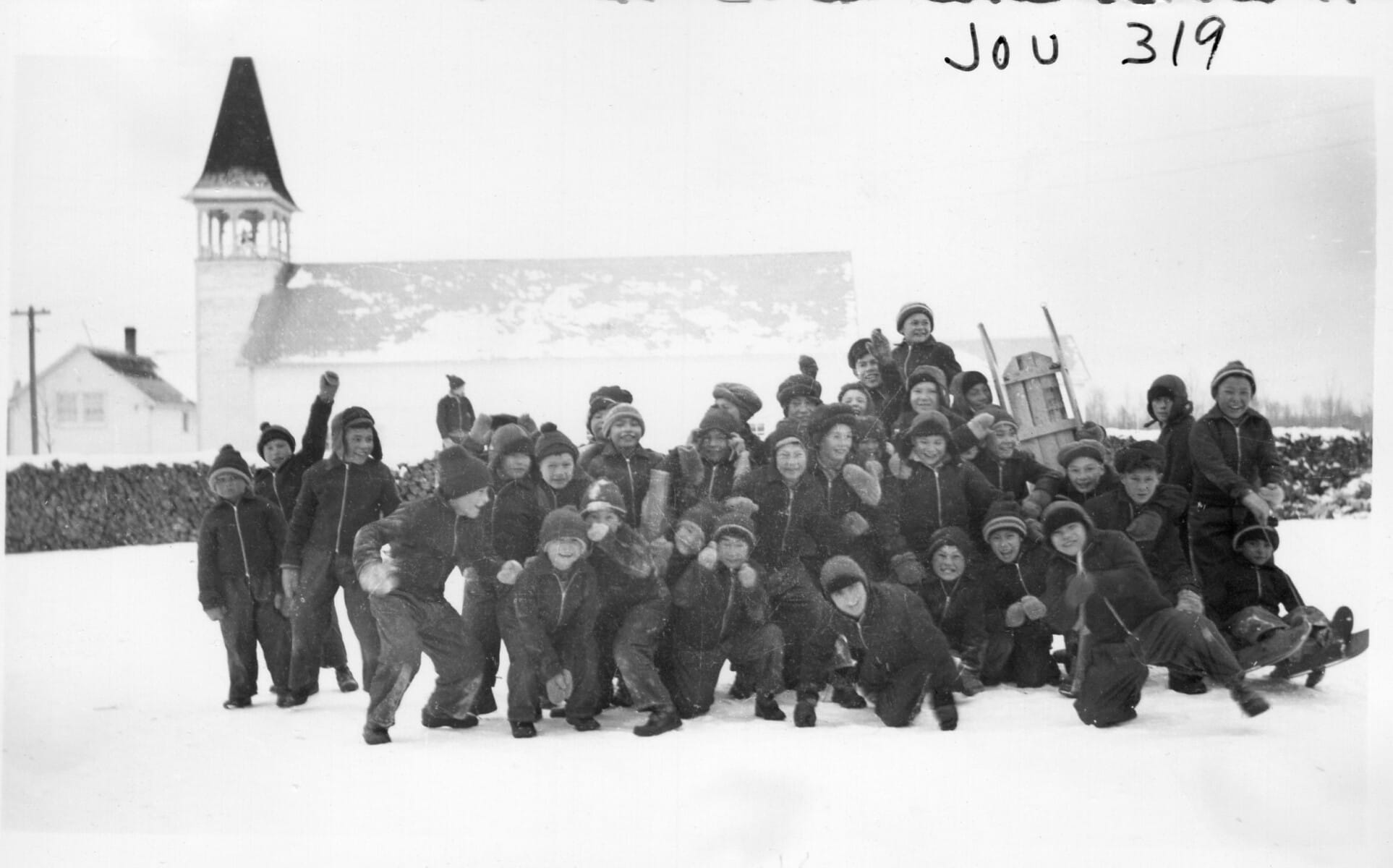

Wilfred went to St. Bruno’s Residential School in the Woodland Cree community of Joussard from 1935 to 1947. He had a typically longer stay than most other students at that time, who usually stayed at the school up to their 8th grade education. But Wilfred had been a resourceful worker on the Joussard mission, experienced from an early age as a teamster with horses and a farm worker. Wilfred’s father asked if he could stay on the mission as a labourer. The Oblates were initially against the proposal, until one of the sisters with a formal education background offered to teach him his Grade 9 and 10 education so he could stay on.

“I started working at the mission when I was 12, doing chores, milking cows, and all the other jobs around the farm,” Wilfred recalled. “Everything then ran on wood heat, and the wood had to be cut in the bush and brought back by a team of horses; and I’ve always been around horses and was always a good teamster.”

Wilfred’s connection to the Sisters of Providence goes back even earlier than his time in the residential school. When he was only three-years-old, Wilfred was saved by the Sisters of Providence thanks to hospital care he received in Grouard. Wilfred’s uncle was a fur trader with the Hudson Bay Company, and he travelled constantly from Grouard to Slave Lake by horse and buggy to foster his trade. When the uncle came through Joussard for a short visit in 1933, he immediately became concerned about young Wilfred, who had just fallen gravely ill. His uncle determined the boy was sick with pneumonia.

“In those days there was hardly any hospitals around. So if you had pneumonia, you had nine days to recover or you were dead,” said Wilfred. “There was only a hospital in Grouard at that time. In fact, people then thought Grouard would become the capital of Alberta, but that’s another story. My uncle was concerned and he took me for a three-hour journey to the hospital in Grouard and that saved my life.”

His life was saved in more than one way. The Grouard hospital also caught fire while Wilfred was recovering there. Though he was only three, he can still remember the sister who had to wrap him into her habit and carry him away from the blaze.

Wilfred received language skills through his education that would come to help him greatly as an adult. Growing up in Joussard, the only languages spoken on the mission were Cree and French. He learned to speak both of these, as well as English through his education with the Sisters of Providence. He can still recall all of the Latin prayers he learned at the school as well.

Later in life, Wilfred would work in High Prairie as an interpreter for the Federal and Provincial Court, thanks in part to the language skills he picked up through his time on the mission.

…

Rosemarie’s family was always close to the religious brothers and sisters that served the north, mainly Oblates of Mary Immaculate and Sisters of Providence. When she was little, Rosemarie always considered the local priest as a part of the family. Her family would wash the priest’s clothes, prepare him lunches when he went travelling, and so on.

She recalls one Danish Oblate who visited her home as he was preparing to depart for missionary work elsewhere in the Peace Country. While conversing with the family, he accidentally leaned against a wall that had just been painted. When he stepped forward, he had a line of white paint streaming down his black cassock – almost like the fur of a skunk. They rushed to wash it so the priest would not miss his train.

…

For both Wilfred and Rosemarie, many of the sisters who taught them also became lifelong friends. One Sister of Providence, Sr. Theresa Devine, taught Wilfred at St. Bruno’s Mission in 1942, and later taught Rosemarie in Fort Vermillion from 1946-1947. And to bring their connection full circle, she ended up teaching their son Will Willier in his Grade 4 class in High Prairie. The sister remained a close friend of the Willier family for the rest of her life. When Sr. Theresa passed away on her 100th birthday, Will wrote a moving memoir in honour of her.

This was only one of many close friendships fostered through their time in the missions.

“I had a nun that was like a second mother to me, Sister Celine,” said Rosemarie. “As a matter fact, shortly before she died she had sent for me. We made it to the Providence Centre in Edmonton to see her just before she passed. They said to her, ‘Rosemarie is here to see you.’ And she had tears in her eyes when she saw us arrive.”

Whether it’s growing up on the missions, working on the railroad, helping build up their local community and much more, the Willier’s have truly lived out the unique history of the Peace Country in vast ways. They are a living link to the history unique to this region and are a testament to its legacy.

Above all, they represent the virtues of a life of service and devotion, and key to it all is the Catholic faith they were raised with.

“I’ve always drawn on that,” Wilfred said of his Catholic faith. “That’s what always led me to say: if I can help, I will help.

“All in all, with all that’s happened in our lives, it has all paid off.”

This is only an excerpt. Read the full story in the January-February 2024 edition of Northern Light