A look back at Catholic cooperativism in Alberta

Evens Lavoie is a living link to St. Isidore’s unique history of cooperative farming

The hamlet of St. Isidore is one of the most unique French settlements in western Canada.

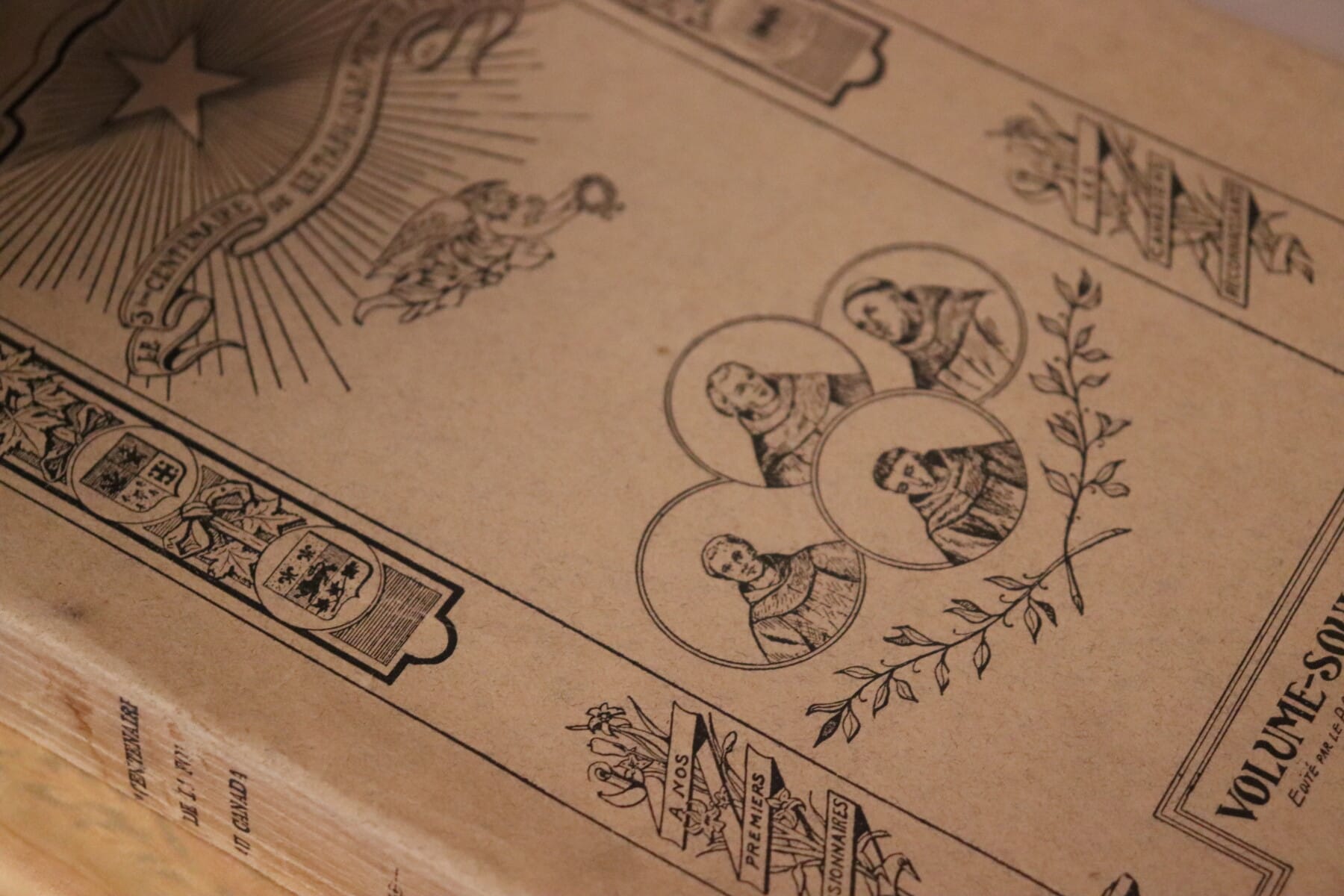

Named after the patron saint of farm workers, it was founded in 1953 by a small group of families from the Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean region of Quebec. The hamlet was established as an agricultural cooperative for families to farm and live together, through the mutual sharing of land, resources, tools, products and profits.

Though things have changed through the years, descendants of those first settlers remain in St. Isidore today, still maintaining some of the culture, traditions and way of life they brought with them. Their cooperative store and post office is still at the centre of the community. The Sunday Mass at St. Isidore Catholic Church still remains entirely in French. The local museum and annual winter carnival continue a rich history of cultural traditions, ethnic dances, and more.

As part of that first train of Quebecois families who travelled to the wooded and muddy terrain that would one day become St. Isidore, senior Evens Lavoie has remained in the hamlet for almost all his life. Today he can point to the black and white photo of his 13-year-old self displayed at the local museum; there he stands alongside his 9 siblings as they wait in the boxcar to begin their new life in northern Alberta.

There were many efforts through the early 20th century to promote migration and settlements in the Peace Country region, where open farm land and opportunity were plenty. The cooperative of Quebecois farmers known as the Union des Cultivateurs Catholiques was one of the groups that set their eyes on the area. This was thanks in large part to the vision of their chaplain, Fr. Gerard Bouchard, who was looking for a way to establish a French Catholic cooperative in Alberta.

“The Peace River region was one of the last to be settled in Alberta,” said Lavoie. “Some of the union executives had first visited the region and prepared arrangements so they could form a parish community here.”

Even priests who were already established in the region were involved in these promotional efforts to bring more French families to the Peace Country, where farm land was widely available and cheap. One of those priests, Fr. Clement Desrochers, OMI helped advocate for families to come establish the St. Isidore hamlet, and some of his own relatives settled there. There were similar efforts in other areas of Alberta as well, such as the St. Paul region.

“There were priests who would come to Quebec and petition people to come to Alberta to establish parish communities. Much of the north was established that way,” said Evens wife Marie Lavoie.

With the initial recruitment efforts of the Union des Cultivateurs Catholiques, seven Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean families had agreed to join the project. They arrived in 1953, with a handful of more families arriving each year until 1960. Evens says the families drawn to the project were already farmers, but they joined hoping these yet unsettled plains of northern Alberta would provide them a better life with much more farmable land.

“My dad had his own operation in Quebec – a dairy farm,” said Evens. “But he came here because it would provide better opportunities, more land and more independence. We were a family of 10 when we finally decided to move, seven boys and three girls, and then they had three more that were born here.”

The family travelled by CN railroad from Quebec to the west, carrying what luggage and belongings they could. This included cows and other livestock, which were sometimes transported in the same boxcars as family members.

When these first families finally arrived in St. Isidore, it did not exactly appear as the land of golden opportunity that had been advertised to them. There was about two miles of dirt road and beyond that it was all untamed and heavily wooded forest. Not only that, much of the soil consisted of “gumbo” – a type of mud that gets stickier and stickier and makes you sink deeper and deeper the more you walk through it. For many, that first walk into the wild terrain that would become their future homes was a difficult one.

Many of these families came from homes with electricity, heat and running water, but now having to build a new life quite literally from the ground up, it was quite an adjustment to make. Marie noted that some families arrived with as many as 16 children who, in the initial years of settling the community, would have to reside in small homes of no more than three bedrooms. Many children would sleep in whatever small open space in the house they could fit into.

For the first months after their arrival, Evens stayed with his siblings at a small apartment in Girouxville, while his father would travel into St Isidore to clear out the forest and begin preparing the farmland. Evens eventually joined to help his father in the summer months.

What was most unique to the founding of St. Isidore was its cooperative farming model. The families, banding together as the “Companion’s Society”, purchased all land, transportation and equipment as a group, worked as a group and reshared the profits in the community and amongst the families evenly. They would also share in ownership of the local schoolhouse.

Especially since Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical “Rerum Novarum” in 1891, attempts to develop economic systems in line with Catholic principles, in large part inspired by the guilds of the Middle Ages, were tried in Catholic societies around the world. Catholic cooperativism was one of these systems, and in Quebec during the 1900s, several cooperative efforts were attempted in farming, factories and credit unions.

…

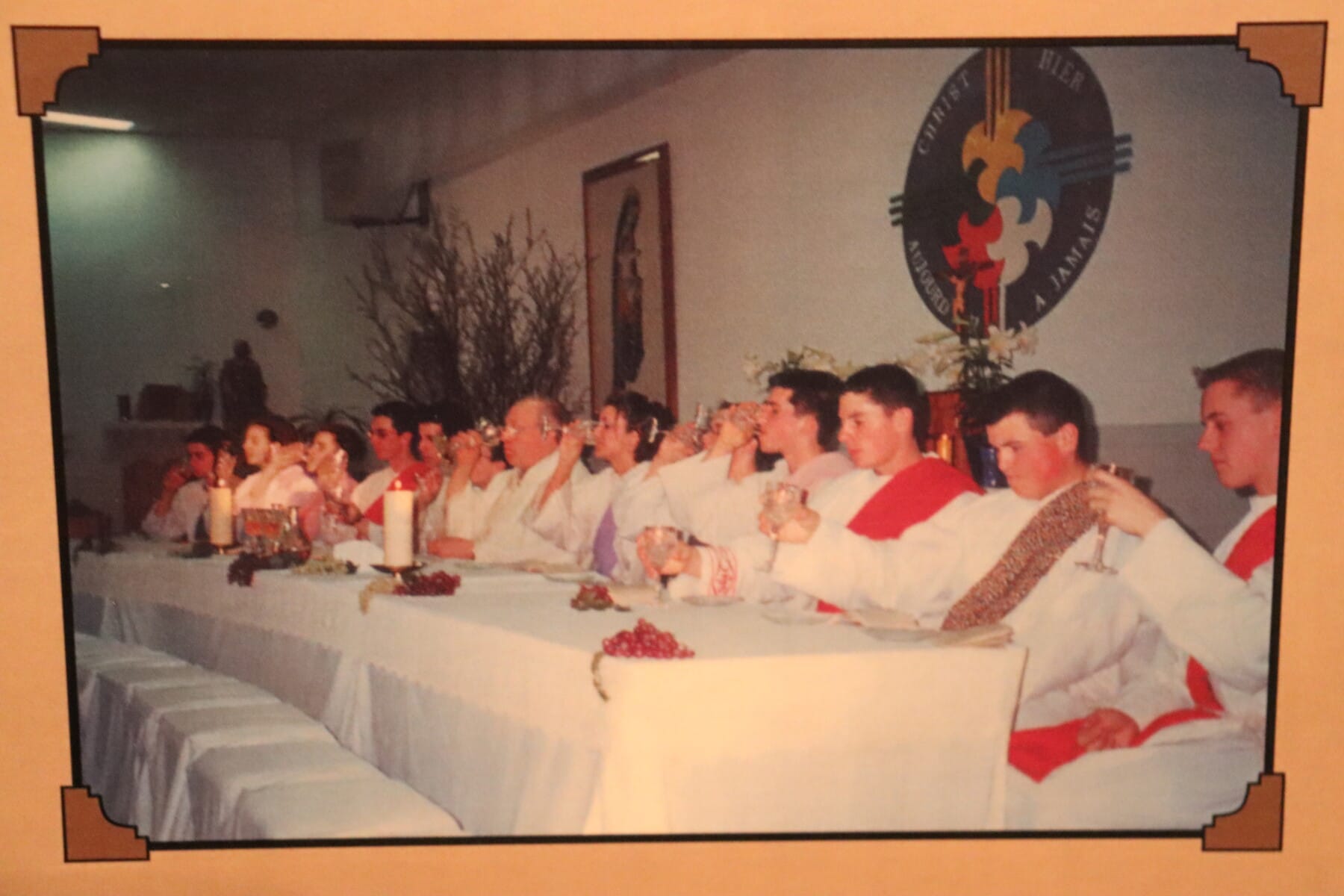

Of the many French communities in the archdiocese, most celebrate bilingual Masses today. However, St. Isidore Church has sought to preserve its liturgy entirely in French. For many, it’s a way of honouring not only their culture and preserving their language, it also honours the Union des Cultivateurs Catholiques’s founding vision for the community.

“It was one of the conditions of the founding of this community that it would be French and Catholic,” said Marie. “And that has been retained in the church. Though there are many in St. Isidore today who are neither French or Catholic. But we are close to two fully English churches in Peace River and Nampa, and being a French community it was important for us to preserve that. We figured if we did do the English-French split we would end up losing our French completely, and that’s not what we are here for.”

Evens began working at the co-op store in 1959 and eventually became its manager, working there until 1992. In 1973, Marie and Evens moved into a house across the street from the store, and they have lived there ever since. They also have two sons who also still reside in St. Isidore. Evens life is thus immensely tied to St. Isidore, having been there from the day the hamlet was founded until the present. At each new frontier and changing way of life in St. Isidore, he remains a living link to this distinct and singular community in the history of Alberta.

This is only an excerpt. Read the full story in the December 2022 edition of Northern Light